At the Menil Campus, a Striking New Drawing Institute Joins the Hub

The $40 million building is the most significant addition to the renowned Menil neighborhood in decades

Nestled within a leafy middle-class residential area in Houston is the Menil campus, a cluster of magnificent—and unexpected—art spaces including the famed Menil Collection and the Rothko Chapel. For the past three decades, international visitors and local art aficionados alike have come in droves to visit the 30-acre arts campus that was the brainchild of oil heiress Dominique de Menil and her husband, John, who, after moving to Houston from France following World War II, became key figures in the city’s developing cultural life.

On November 3, the highly anticipated Menil Drawing Institute joined the hub. The 30,000-square-foot, $40 million building is the world’s first freestanding museum entirely dedicated to the exhibition, acquisition, conservation, and storage of drawings. It is also the first building added to the Menil campus—which, in addition to the Renzo Piano–designed Menil Collection (1987) and the Rothko Chapel (1971), includes the Cy Twombly Gallery (1995), the site-specific Dan Flavin Installation at Richmond Hall (1996), and the Byzantine Fresco Chapel (1997)—in more than two decades.

“The building marks an exciting new chapter,” says Menil director Rebecca Rabinow, who joined the institution from the Metropolitan Museum of Art in 2016. “The quietly innovative architecture of the museum allows us to make drawing, the most intimate of all artistic practices, accessible as never before.”

Drawings have always been of central importance to the Menil’s 17,000-piece collection, and the idea for the new addition was conceived almost a decade ago by the Drawing Institute’s founder, Bernice Rose. Plans kicked off in earnest in 2009, when David Chipperfield Architects was commissioned to create a master site plan, and two trustees, Janie C. Lee and Louisa Stude Sarofim, who each promised 55 drawings from their noteworthy private collections, championed the project. The buzz-worthy Los Angeles architecture firm Johnston Marklee, known for its distinctive, beautifully proportioned spaces, was selected in 2012 to lead the design.

Recommended: Take a Tour of the Newly Expanded Glenstone Museum

Visitors to the institute are greeted by an airy, modernist structure crafted in elegant, painted white steel and stained cedar. There are four primary components: the exhibition gallery, a drawing room used by scholars and researchers, a state-of-the-art conservation lab, and a flood-proof storage room. The so-called Living Room, which also serves as the entry, unites the north and south sides of the building and is flanked by two sun-dappled, Japanese garden-inspired courtyards designed by Michael Valkenburgh Associates.

“We spent time visiting many museums,” architect Mark Lee tells Galerie. “What we found was that drawings were usually relegated into galleries that had to serve multiple purposes—for painting and sculpture and so on, sometimes with 16-foot ceilings! Drawings are unique; they can be intimate, and you need to get close.”

Inspiration came from a variety of places: from Sir John Soane’s Museum and the Dulwich Picture Gallery in London to liturgical and religious structures such as medieval monasteries with their private cloisters and Shaker meetinghouses. But the biggest influence was the personal history of the Menils. Lead architects Sharon Johnston and Mark Lee looked closely at the seminal buildings that the couple built and visited their home, designed in 1950 by Phillip Johnson. “We were inspired by the Palm courtyard and the interesting dialogue between inside and outside,” says Lee. “It was important for us to expand on that lineage.”

The architecture works in perfect harmony with the rest of the campus as well as the surrounding Arts and Crafts–style residential bungalows. “Given the proximity of the houses, Renzo Piano said he wanted his Menil Collection building to feel small on the outside but big on the inside,” explains Johnston Marklee project manager Nicholas Hofstede. “But we wanted to do the opposite. We wanted it to look much bigger but feel intimate when inside.”

Recommended: Rare Works by Jasper Johns go on view at The Broad in Los Angeles

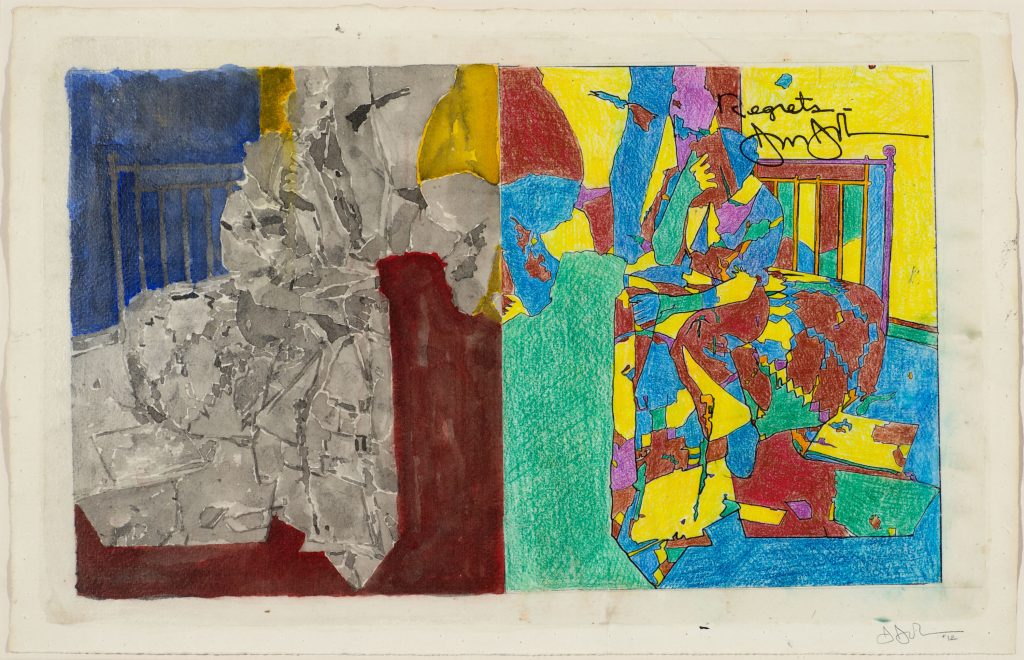

The inaugural show, “Jasper Johns: The Condition of Being Here,” on view through January 2019, sets the ambitious tone for what is to come. It features 41 works by the American icon spanning 1964 to 2016, which reveal not only the artist’s lifelong fascination with certain motifs, including maps, flags, and targets, but also, most important, how he pushed the definition of the medium. There are works in pencil, charcoal, watercolor, ink, and even Mylar, a type of polyester film. In Study for Skin 1 (1962), the artist covered his face and hands in oil before impressing them on the surface the paper in a ritualistic-like performance, and Flag on Orange Field (1957) reveals his remarkable mastery of markmaking. The works “stretch the definitions of what drawing can be,” says Rabinow.

Other attempts to expand the boundaries of drawing are Ruth Asawa’s Untitled (Hanging Six-Lobed, Discontinuous Surface with an Interlocked Top Section), 1956, which hangs from the ceiling like a drawing in space. Nearby is a massive screen print mural by Roni Horn, who is the subject of the next exhibition, in spring 2019. Outside is a monumental reinstallation of Michael Heizer’s, Rift and Dissipate, a series of steel lines originally built in Nevada’s Black Rock in 1968. “Dominique would talk about spirituality, and I think it now gets confused to be about religion,” says Rabinow. “It’s not about religion. It’s about the spirituality she felt in art. She meant there is something in it that can feed the soul.”

The main Menil Collection building, which houses a varied collection spanning Central and West African art to European Surrealism has also reopened after a major renovation and reinstallation with refinished floors and a rehang of the collection that highlights many works that had never before been displayed. “We are committed to the founders’ belief that art is essential to the human spirit. We foster direct personal encounters with art, and that means always being free of charge,” Rabinow explains. “Things do not stay still, and the collection continues to grow.”