Highlights from Contemporary Istanbul 2017

This year's Contemporary Istanbul art fair is a symbol for the city's social and cultural changes

At the top of Istanbul’s Maçka Sanatçılar Park, you can see busts of Turkey’s past rulers. Situated atop white plinths on the red brick ground, the metallic faces of Atila, Osmanbey, Ataturk, and the rest of their coterie circle visitors, surrounding them with the story of the country’s past leadership.

A short walk downhill, however, presents visitors with a newer facet of Turkish history. A temporary exhibition entitled “The Fifth Element,” a project for the 12th edition of the Contemporary Istanbul art fair. It is the first ever outdoor contemporary sculpture at the event, and features a group of nine sculptures by both local and foreign artists. Turkish artist Günnur Özsoy, for example, erected three all-white, polyster forms that rise out of the ground like ghosts. Jannis Kounellis, the recently deceased Arte Povera artist, created a large iron box within another large iron box, holding colorful old tiles. The celebrated British sculptor Tony Cragg, meanwhile, presented his monumental twisted sculpture, “Must Be,” that became a popular resting place for one of the city’s many feral cats.

This striking juxtaposition of old and new, civic pride and global outlook, is everywhere in the city. Riding along the Bosphorous from the Istanbul Modern art museum (one of the sites for the recently opened Istanbul Biennial) to the Sakıp Sabancı Museum where a massive Ai Weiwei retrospective is on view, you pass the Ciragan Palace Kempinski hotel (a beautifully restored Ottoman palace), and the Baroque splendor of the Ortaköy Mosque.

Small wonder, then, that the fair itself focused both on the Turkish gallery scene and a slew of new international galleries, spearheaded by London-based curator and collector Kamiar Maleki (the eldest son of Iranian-born, London-based mega-collectors Fatima and Eskandar Maleki).

This year, 73 galleries from more than 20 countries participated. At the preview, chairman Ali Güreli referenced the coup attempt and terror attacks of the previous two years and expressed hope that the city will recover and develop into a major art destination. While he spoke, fair employees made last minute preparations, laying turf along the floor. “Parks used to be the focal point of the city,” said Maleki, hoping that the fair’s home, the Istanbul Convention and Exhibition Center, would become another such congregation venue. If a tad gimmicky, the turf represented a fine sentiment.

Galerist, one of the leading contemporary art galleries in Turkey, showed a work by Nil Yalter that offered one of the most explicit references to the political situation in the country. Entitled Exile is a Hard Job, the installation featured a linen sheet printed with photographs of Turkish immigrants to Paris with its titular message running across the top right corner in red neon lettering. Yalter herself is something of an exile, a Turkish feminist artist who’s lived in Paris since 1965.

She first created the work in the 1970s, but unfortunately, the themes have remained relevant. Not far from the art fair, Syrian refugees wandered the streets. (There are currently around 3.5 million refugees housed in Turkey under an EU agreement.) Gallerist Müge Çubukçu spoke of the creative output in times of political and social unrest. “I think it’s a very productive era for artists,” she says. “I think there’s going to be a booming production afterwards.”

New international galleries included Maximillian William, who runs a roving space out of London and describes himself as a “21st Century nomadic gallerist.” As if to complement his own youth and novelty, he mounted a solo exhibition of delicate, minimal works on paper by on-the-rise Polish artist Magda Skupinska, who was born in 1991.

Both William and the director of Accra’s Gallery 1957 El-Yesha Puplampu (another newcomer, and only founded in 2016), cited Maleki himself as a major reason for participating in the fair. “We position ourselves as an international gallery located in Accra. So we’re not just a regional gallery that’s focusing on collectors within our area,” Puplampu says.

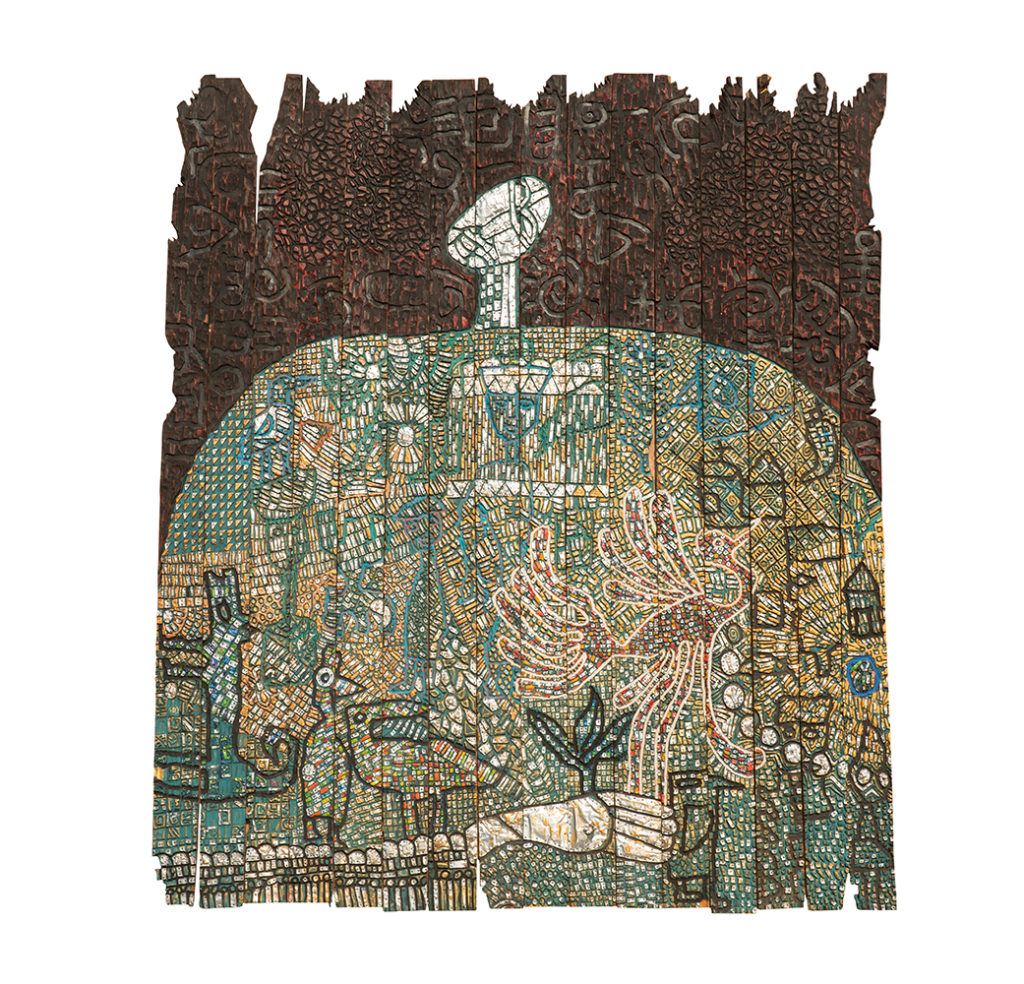

Istanbul’s Galeri 77 exhibited works by Armenian artist Armén Rotch that served as a visual metaphor for global connection. After posting an advertisement in a newspaper asking people to send him used tea bags, Rotch received more than he’d ever imagined, from countries around the world—millions, says gallerist Buğra Uzunçelebi. Collaged together, the used tea bags—many in shades resembling human skin color—symbolize cultural interchange, ritual, and consumption. Not a terrible metaphor, either, for an art fair itself.