How Tom Stuart-Smith Conjures Extraordinary Gardens Around the World

The English landscape architect has conceived a diverse array of naturalist settings from Wisconsin to Windsor Castle to the medina of Marrakech

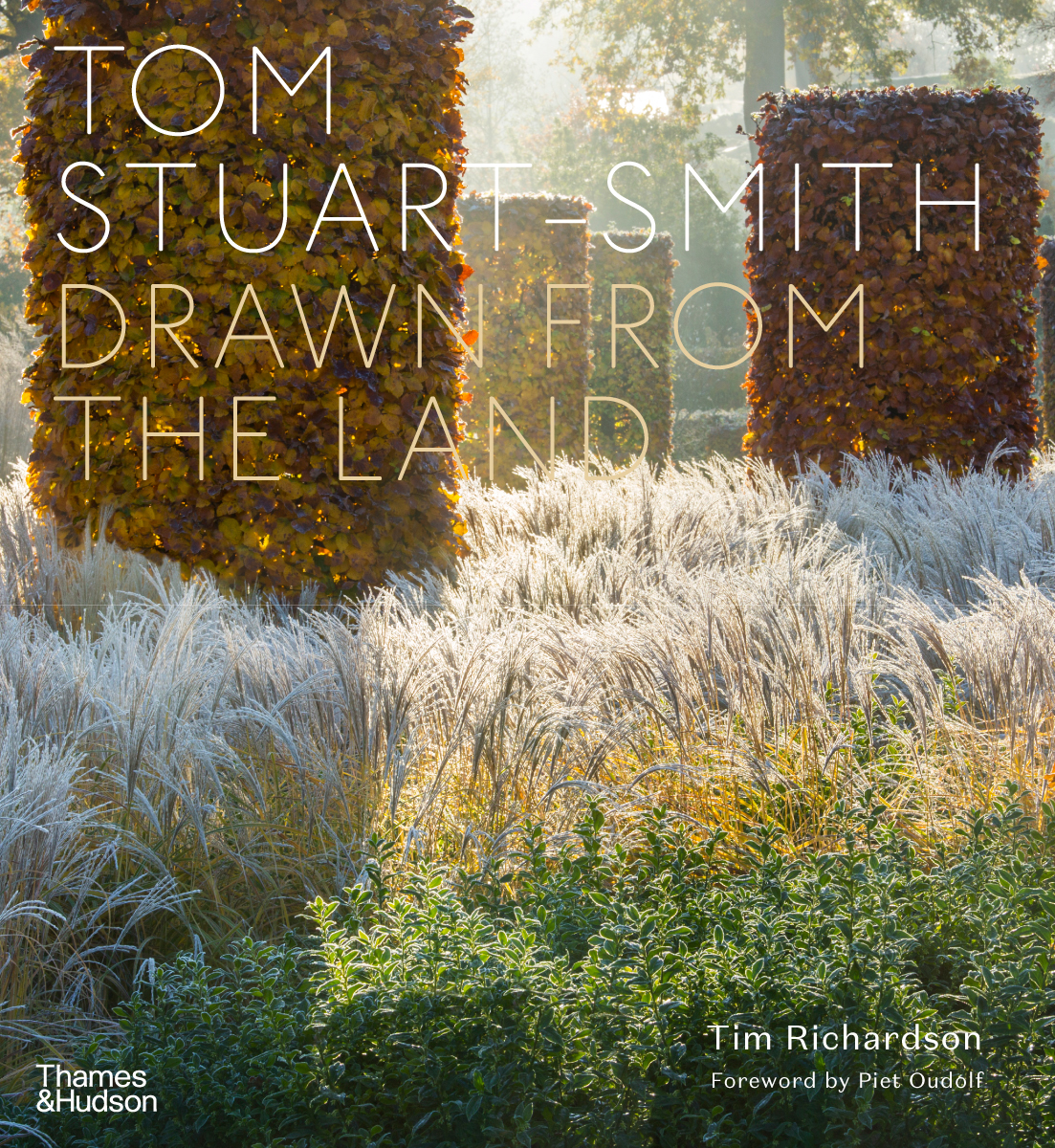

The book cover. Photo: Courtesy of Thames & Hudson

Since launching his namesake firm in 1998, English landscape architect Tom Stuart-Smith has conceived naturalist environments that perfectly complement a diverse array of settings, from Wisconsin to Windsor Castle to the medina of Marrakech. “I’m interested in making people take time to become more aware of nature,” he explains. “Gardens should be transformational spaces that stop you in your tracks.” So much is evident in his first comprehensive monograph, Drawn from the Land (Thames + Hudson), which comprises two dozen of his most arresting projects. However, it’s his own enthralling property, which is set in the Hertfordshire countryside, that best embodies this philosophy. “When my son was born there were just sticks in the ground, and now there are things he can climb onto,” he says. “You create a landscape, and it ends up creating you.”

Read below for our Q&A with Tom Stuart-Smith.

Yotes Court. The parterre planting – persicaria, Euphorbia cornigera, Salvia nemorosa ‘Amethyst’, Helenium ‘Moerheim Beauty’ – with the pool building by Sergison Bates beyond. Photo: Allan Pollok-Morris

Galerie: How does color factor into your designs?

Tom Stuart-Smith: Color is last thing I think about. One of reasons I draw projects in pencil, which I always do at beginning, is that I don’t want my clients to start thinking about colors and plants until quite a late stage. Particularly in the U.K., people are quite plant crazy. It’s very easy to get stuck in a conversation about plants before knowing what the garden is going to be. So, rather perversely, I want to think about atmosphere, sequential nature, narrative, and overall composition of how it relates to context first. Color is really important to me, but some of my favorite pictures might be taken in winter or with really quite subdued coloring. I’m not somebody who uses very artificial colors.

The Barn at Stuart-Smith’s residence. Photo: Andrew Lawson

What has been your most rewarding project?

Every job faces a different kind of challenge so to choose between them is difficult. I have to say a favorite is my own garden, because it’s the one of the closest to name, part of family life, and most remarkable in my life. My wife, Sue, has written this amazing book about the impact of gardening on our culture. We came to live here in our mid-20s, and we have been here for 35 years. When we came here, we were living in this beautiful, 17th-century timber barn surrounded by 50 acres of wheat. We made this garden out of nothing, out of soil, and it has grown at same time as our life has changed and our children have grown. My son is here this evening. When he was born the garden was sticks out of ground and the trees are now things he can climb and there’s something rather wonderful about that. You create a landscape, and it creates you. It has a profound effect on your behavior for your whole life. It becomes the rose-tinted spectacle through which you see the world.

Oakhill. Drawn over the American meadows, with species including Echinacea pallida and E. paradoxa, and Silphium laciniatum and S. terebinthinaceum. Photo: Allan Pollok-Morris

Do you have a favorite species of plant?

I would say the plant which means most to me is the European oak tree because its such an extraordinarily strong part of the landscape. Some of the biggest ones are over 1,000 years old. The house that I’m living in is made of it. It’s what made the British Empire—all of the ships were made out of it. Most of the great medieval buildings are made of it. It’s kind of inextricably linked to our culture. In the garden here I’ve planted more oaks than any other species. I want it to be part of the landscape in which it finds itself. I think it’s about loving what’s familiar. Of course I love the latest fancy plant that comes from mountains of Vietnam, but that’s more of a fleeting, fashionable thing. My love for oak trees is something that is entwined with culture and memory.

Mount St John in Yorkshire, UK. One half of the garden at Mount St John. The yellow tones of phlomis, digitalis and eremurus dominate the upper level, while below the pool the planting becomes darker and richer. Photo: Andrew Lawson

Do you see plants as architecture?

I definitely do not see plants as architecture. I see them as the antidotes of building blocks. I’ve always seen gardens as kind of a dialectic meeting of the animate and inanimate. The living and the dead. And the one is a kind of antidote to the other. There’s a sort of annual automation between the domination of nature and domination of the idea of a garden then overcome by nature. It’s always been fascinating to me; increasingly as I get older, I’m more interested in the idea of a garden as a malleable whole. That’s because I’m more aware of the carbon footprint in making a big garden. I do feel the holy grail of gardening is looking after a plot and making something which is perhaps rather simple and bland into something complex and multi-layered, changing, and that elicits different responses to different people. My work is more about process than creating a fixed product. Clients recognize that a garden is a changing thing, something a designer sets on a path that will have a slightly unpredictable journey.

Moor Hatches in Wiltshire, UK. The walled swimming pool garden, with its distinctive thatched wall and perennial plantings including, in the foreground, Phlox paniculate ‘Franz Schubert’ and Echinacea purpurea ‘White Swan’. Photo: Allan Pollok-Morris

What is your goal?

I’m interested in the idea of making people take time to become more aware of nature. In many ways that’s what gardens do. They should be a communication of external space. They shouldn’t be places full of things—they should be transformational spaces that stop you in your tracks and think I’ve never been in place like this. With the Oak Project at the Yorkshire Sculpture Park, the first artist commission we are doing is an environmental sculpture by Studio Morrison. The piece is called Silence–Alone in a World of Wounds, and it’s a cloister made out of decaying, biodegradable materials like thatch, timber, and rammed earth. The whole thing will eventually fall apart. But without that frame around it, it seems mundane. By putting it in a frame, it’s become something remarkable for people to think about the beauty of this clump of trees.

House in Kottayam in Kerala, India. The main tank, with the pool building visible in the trees beyond. Photo: Derry Moore

A version of this article first appeared in print in our 2021 Summer Issue under the headline “Field of Dreams.” Subscribe to the magazine.

Broughton Grange in Oxfordshire, UK. The lower terrace, with miscanthus in the foreground and the trees of the wider garden beyond. Photo: James Kerr